System of Dallas Government

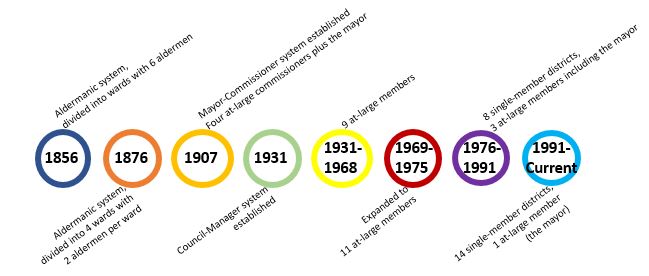

Since its incorporation in 1856, the City of Dallas has implemented the following three governance methods:

—1856: Alderman system, with six aldermen

—1907: Mayor-Commissioner system, with four commissioners covering streets and public property, finance and revenue, police and fire, and water and sewage

—1931: Council-Manager system

• 1931-1968—9 at-large members

• 1969-1975—11 at-large members

• 1975-1991—8 single-member districts plus 3 at-large members

The following image shows the progression of governments in Dallas.

Demographics

The following population breakdowns are included for reference during the years just before and just after the 14-1 decision. Numbers are from the Federal Census. The 1970 census does not include a specific Latino division in its population characteristics. With only 1% in the Other category, the Latinos of that year's census are likely included as whites.

1970

| 844,401

| 25%

| -

| 74%

| 1%

|

1980

| 904,078

| 29%

| 12%

| 57%

| 1%

|

1990

| 1,006,877

| 29%

| 21%

| 48%

| 2%

|

2000

| 1,188,580

| 26%

| 35%

| 35%

| 4%

|

Government-Supported Segregation

Dallas' history of discrimination at the City Hall level is long and specific, and in 1975, US District Judge Eldon Mahon noted that, among other matters,

• the . . . charter for the City of Dallas written in 1907 contained a section entitled "Segregation of the Races." This section was amended through 1952 and was carried forward as part of the charter until it was repealed in 1968. This section authorized the City Council to pass city ordinances providing for the use of distinct blocks, for the housing, amusement, churches, [and] schools, by members of the "white" and "colored" races.

• in 1937, the City Council passed on ordinance regarding separate spaces in commercial motor vehicles for white and black passengers. A penalty was established for those who rode in spaces not designated for the race of the individual involved.

• in 1942, the City Council adopted a resolution which enumerated the requirements which a taxi cab owner must have met before the cab would be permitted to carry Negro passengers.

• in 1961, the City Council agreed to contract for the engaging of ambulance service and burial of Negro paupers. *

Citizens Charter Association

In Dallas, candidates for elections have historically not run on traditional party lines, and the Republican and Democratic Parties did not field specific candidates. Instead, groups such as the Citizen's Charter Association (CCA) controlled City Council elections as a "non-partisan slating group". The CCA grew out of a reform movement in the 1930s when Dallas adopted its Council-Manager form of government. In principle, the goal of the CCA, run by Dallas businessmen, was to correct abuses of the commission form of government by incorporating citizen participation into governmental affairs.

The CCA had an 85% success rate for its candidates winning Council seats, and the supposedly apolitical CCA had never endorsed a black or Latino candidate for City Council. The CCA's hold over Dallas candidates was viewed as another obstacle for non-whites reaching City Hall.

In the 1960s, the CCA recognized that the black and Latino population had grown significantly, and these citizens were expressing their displeasure about their lack of representation. In 1967, the CCA agreed to increase the size of the City Council from nine to 11 and include two minority positions. To that end, the CCA then supported George Allen and Anita Martinez—one black and one Latina—for City Council. Martinez and Allen became the first non-white Councilmembers for the city, but this CCA backing was more a granted

permission for blacks and Latinos to serve than the legitimate patronage that white Dallas candidates saw. Before Allen and Martinez were green-lighted, the CCA had first determined that more-desired white candidates were not available for the seats.

Lipscomb v. Wise

In 1971, Al Lipscomb and Elsie Faye Heggins, joined by other community leaders. filed a lawsuit against Mayor Erik Jonsson and all other members of City Council. The suit, Lipscomb v. Jonsson, requested a postponement of the April 6, 1971, City Council election until the "dilution of racial minority voting strength" was ended. The suit,

Lipscomb v. Jonsson, was dismissed at the time, however, for failure to state a claim upon which relief could be granted.

On appeal, the Fifth Circuit remanded with clarification of what plaintiffs' burden would be, and, the case, now

Lipscomb v. Wise after Wes Wise was elected mayor, went to trial in 1974. A former Dallas city planner testified that, based on federal census analysis, Dallas was one of the most segregated cities in the country because while black Dallasites comprised more than 20% of the population, 90% of those citizens lived essentially within the same neighborhoods. The planner stated that it was an extremely segregated residence pattern while then-City Attorney Alex Bickley denied the claim, saying that the less-than-equal representation was a matter of interpretation.

Judge Mahon ultimately ruled that the City of Dallas at-large system was unconstitutional because

when all members of the city council are elected at large, the significance of this pattern of blacks carrying their own areas and yet losing on a city wide basis is that black voters of Dallas do have less opportunity than do the white voters to elect councilmen of their choice. Another shadow of dilution is found in the high correlation between endorsement by the [Citizen's Charter Association] and victory city wide. Meaningful participation in the political process must not be a function of grace, but rather is a matter of right.*

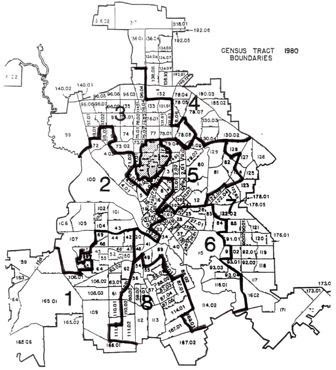

In 1975, as the result of the lawsuit, Dallas moved from 10-1 to an 8-3 plan, whereby voters elected eight single-member district council members and three other at-large members (one of those being the mayor). The 8-3 system was used for all Dallas City Council elections from Judge Mahon's decision in March 1975 through the 1979 Council elections (although the single-district lines were redrawn in 1979 and in 1982). The following image shows the 8-3 zoning district map from 1980:**

Williams v Dallas

By the late 1980s, Latin and black minorities made up almost half the city’s but were unable to elect more than three members (black or Hispanics) to the council. In 1988, Marvin Crenshaw and Roy Williams and filed a lawsuit to have the 8-3 system ruled unconstitutional because it diluted minority voting strength. During the deposition phase of the suit in September 1988, six of 11 council members testified that the existing 8-3 election system was equitable and afforded equal access to all Dallas citizens for fair representation at City Hall. Thousands of citizens disagreed.

In 1989, Mayor Annette Strauss created the

Dallas Together commission and charged it with the "difficult task of finding ways to reduce the racial tensions in our community" by breaking down barriers of "prejudice, racism and classes. "^

Contrary to the views of the Council as a whole,

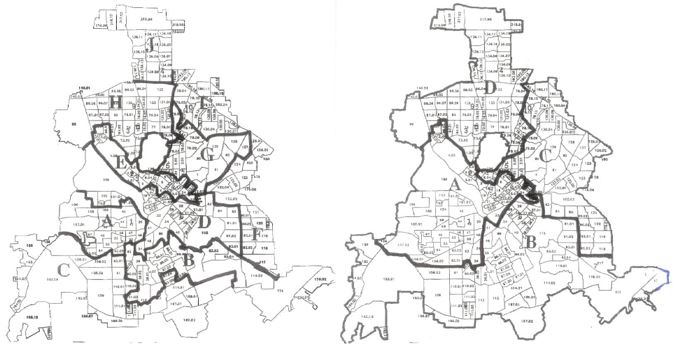

Dallas Together concluded that the 8-3 system was unfair. A then-created Council Review Committee considered both a 12-1 and a 10-4-1 plan and opted to support the 10-4-1 system, even though this proposal projected a lower percentage of black representation than the City Council could have achieved by redrawing the 8-3 lines. This system was narrowly adopted after a bitter and divisive charter election in August 1989, with most blacks opposing the plan. The following two images show the 10 single districts and four at-large districts.**

The 10-4-1 plan, however, was never used because the City’s 8-3 plan was ruled unconstitutional in March 1990. Thinking that the 10-4-1 plan would also be unconstitutional, the City Council put a 14-1 plan, where only the mayor would be elected “at large”, on the ballot. It was defeated by 372 votes in December 1990. In May 1991, the US Department of Justice rejected the city’s 10-4-1 plan.

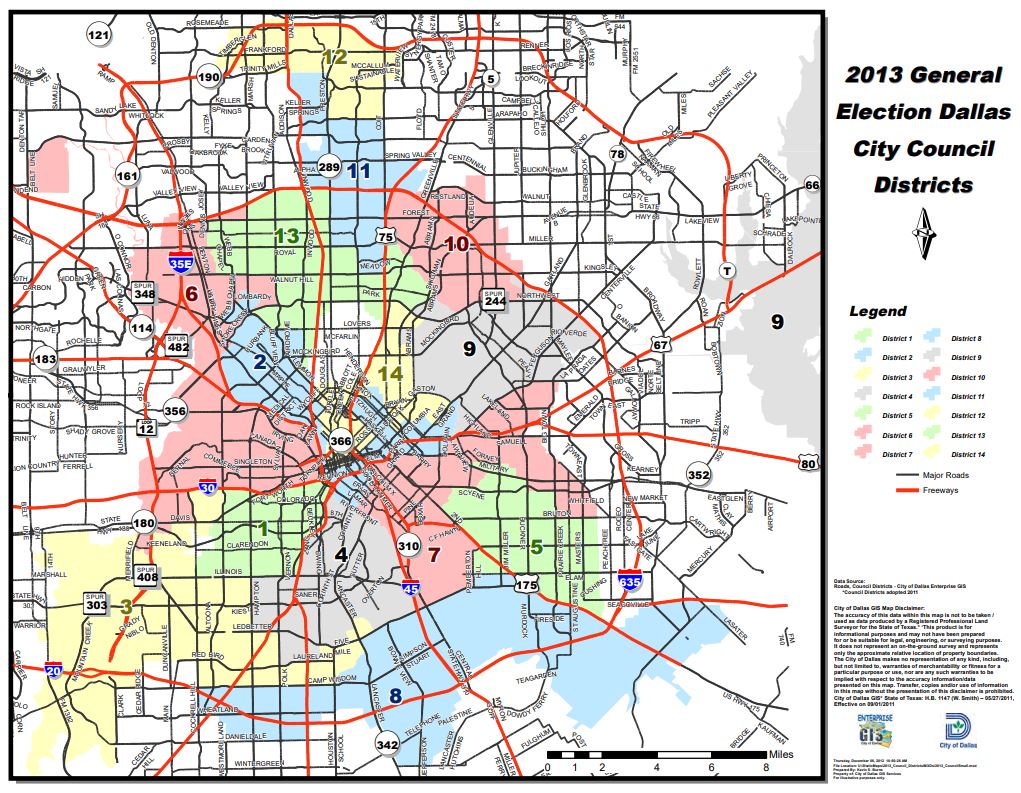

Judge Buchmeyer then held a remedy hearing in January 1991 during which he directed the city’s appointed redistricting commission, the city’s demographer, and a demographer designated by Williams and Crenshaw to draw a 14-1 plan for the court using the new 1990 census information that reflected a black population of 29% and a Latino population of 21% of the Dallas population.

The following image shows the fourteen-district zoning map from 2011.

The City of Dallas used computer models that enabled the redistricting staff to split voting precincts and census tracts to achieve the racial composition desired in each district. Using the 1990 census data, the commission drew lines so that the population in the planned minority districts was about 65% of that particular racial or ethnic group. The Atlas of Split Voting Precincts in the City of Dallas (Collection 1992-027) was created during the 14-1 redistricting process.

Questions still exist about the success of 14-1 and its implementation. Some citizens feel that the plan created 14 fiefdoms whereby the Councilmember only votes for and considers the lives of that district's constituents versus contributing the greater good of Dallas. Others feel that the districts are too gerrymandered to truly dissolve North Dallas' hold over city politics and finances. And quite a few feel that the plan is working well. However, the citizens spoken with for this project agree on their desire that Dallas voters would use their voices and go to the polls on election days - all election days.

____________________________________________________________________________

*Lipscomb v. Wise, 399 F. Supp. 782 (N.D. Tex. 1975)

^Williams v. City of Dallas, 734 F. Supp. 1317 (N.D. Tex. 1990)

**Districting images courtesy former City Councilmember Chris Luna