This online exhibit contains governmental history, 14-1 details, involved voices, and images of Dallas politics leading up to the game-changing ruling that

came to be known as the 14-1 decision. It is dedicated to Roy Williams and the countless other citizens of Dallas desirous of receiving equal representation, for all Dallasites, from the City Council.

Exhibit background

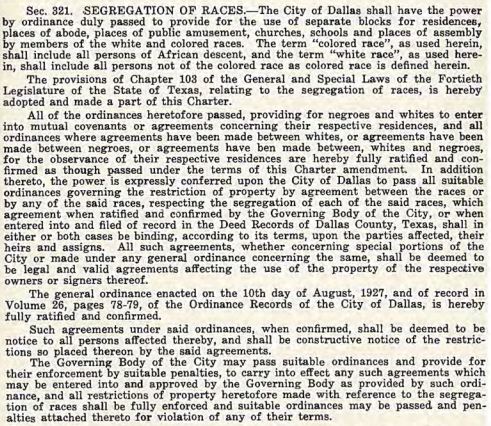

The population of Dallas has contained blacks, whites, and Latinos since its earliest days. City leaders, however, have not equally represented Dallas' citizens' neighborhoods and needs. Racial, financial, and geographical issues have impacted the political debates on economic, education, and social welfare programs. Blacks were restricted from serving on the Dallas City Council for Dallas' first hundred years. For most of the twentieth century, the City Charter contained a Segregation of Races section that authorized the Council to divide Dallas into specific areas for whites and the colored races. The following text shows the language of the 1931 City Charter; this section was not removed by City Council until the 1968 charter revision.

Permanent change

In 1991, the system of Dallas government was forever changed when Dallas was redistricted into fourteen single-member voting areas. The fourteen districts could elect their own representative to City Council, and the one at-large seat would be held by the mayor and elected by all the citizens of Dallas.

Marching on City Hall in support of the 14-1 Council

Photo courtesy Diane Ragsdale

How did Dallas get to that fifteen-person ballot for the November 1991 election? A lawsuit.

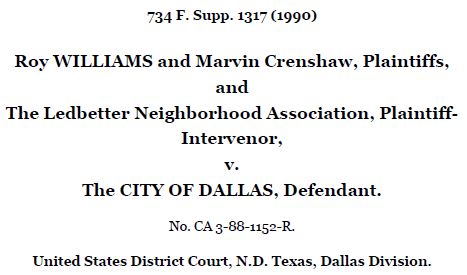

In May 1988, lawyers Betsy Julian and Mike Daniel filed a lawsuit on behalf of Roy Williams and Marvin Crenshaw. The suit argued that the existing system of eight single-member districts and three at-large seats discriminated against blacks. The Ledbetter Neighborhood Association, a group of Latino residents from West Dallas, joined the suit later.

Timeline of the Path to 14-1

Roy Williams and Marvin Crenshaw v The City of Dallas was filed in 1988, but the black and Latin citizens of Dallas began overtly pushing for change in the 1960s. The following table shows highlights of those activities. More details are provided on the governmental and 14-1 history page of the exhibit.

| 1969 | 10-1 Council was eleven council places, including the mayor. All places were elected at-large. Two seats were reserved for minorities. Anita Martinez and George Allen won those seats giving the Mexican-American and black populations their first elected City Council members.

|

| 1971 | The first case against Dallas' at-large system of electing council members was filed by Al Lipscomb and seventeen other plaintiffs. The suit, Lipscomb v. Jonsson, was dismissed for failure to state a claim upon which relief could be granted. |

| 1975 | The lawsuit, now Lipscomb v. Wise after a change in Dallas mayors, was addressed under appeal in 1975. U.S. District Judge Eldon Mahon ruled that the City of Dallas at-large system was unconstitutional because it diluted the black vote. The city used an 8-3 system, under which the mayor and two City Council members ran citywide and eight others ran in single-member districts. Mahon permitted the city to determine a new plan. |

1976

| The 8-3 mixed plan won approval and became part of the City Charter on April 13, 1976.

|

1979

| Lipscomb v. Wise concludes after almost a decade of litigation. By this time, two blacks, but zero Latinos, had been elected by single-member districts. At the insistence of the Justice Department, Dallas created a third minority district by redrawing the lines in a 45.11% black and 24.3% Latino distribution.

|

1981-82

| Council Member Elsie Faye Heggins led a move to study maps and demographics then reapportion the existing eight districts. In seven of the 11 reapportionment plans produced by the city, it was evident that the Council could create not only three black-majority districts but also a fourth swing district with a minority population over 50%. All proposals met with immediate opposition, but on March 24, 1982, Council passed Ordinance 17346 and reapportioned the eight districts.

|

| May 1988 | Roy Williams and Marvin Crenshaw filed a federal voting rights lawsuit, contending that the city's election system dilutes minority voting strength. The Ledbetter Neighborhood Association, representing Latino residents, joined the plaintiffs asserting that the 8-3 plan "also discriminated against Mexican-Americans." |

| August 1989 | In a referendum, voters approved a 10-4-1 election system, which provided for 10 single-member districts and four regional seats, with the mayor elected at large. Most minorities opposed it, and the U.S. Justice Department did not approve the plan. Elections were not held using it. |

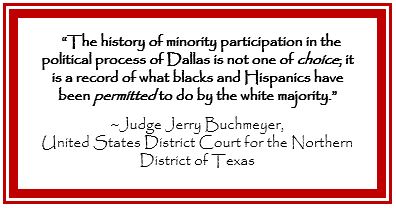

| March 1990 | U.S. District Judge Jerry Buchmeyer wrote that minority participation in Dallas politics had been a question of "what blacks and Hispanics have been permitted to do by the white majority" and struck down the city's 8-3 election system. |

December 8, 1990

| Voters rejected the Council's initial 14-1 plan 45,624 to 45,252 (372 votes).

|

| February 1991 | Judge Buchmeyer ordered elections held May 4, 1991, using a 14-1 plan. The City Council voted to appeal his ruling to the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in New Orleans. |

| March 1991 | The City sent a 10-4-1 map to the Justice Department for the pre-clearance required under the Voting Rights Act. The 5th Circuit stayed Judge Buchmeyer's ruling to give the Justice Department a chance to review the merits of 10-4-1. |

| May 1991 | The Justice Department did not approve 10-4-1. |

| August 1991 | Judge Buchmeyer ordered elections on November 5, 1991, using the 14-1 plan. |

| November 1991 | The first elections under the 14-1 plan were held. Nine whites, four blacks, and two Latinos were elected to represent Dallas. This Council included four women, also a first for Dallas.

|